Social engineering attacks are on the rise in higher education. In 2017, Canada’s CBC News reported that MacEwan University in Edmonton was defrauded of $11.8 million after a staff member fell victim to a phishing attack; a popular social engineering tactic. In the email, the social engineer impersonated a vendor requesting a change in banking information. Because the staff member didn’t verify the email and the request, the school lost millions of dollars.

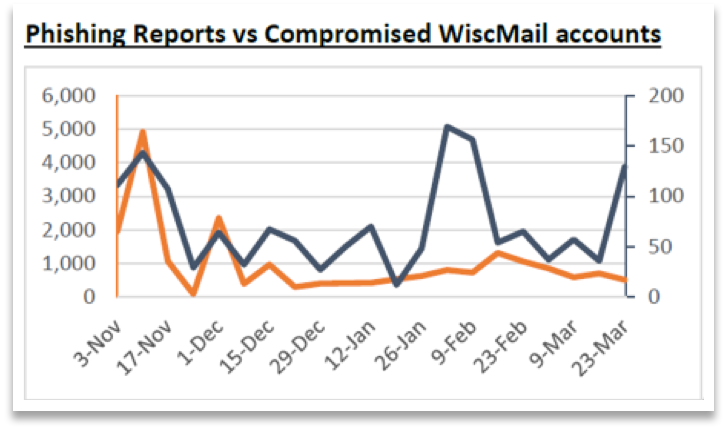

Here at UW-Madison we experience compromised credentials and phishing attempts on a regular basis. As you can see, when you overlay phishing attempts with compromised credentials you typically see corresponding spikes in compromised email accounts. In the graph below the orange line represents the most recent weekly data on number of reported phishing attempts on campus and the blue line represents the number of compromised email accounts from that same week.

Here at UW-Madison we experience compromised credentials and phishing attempts on a regular basis. As you can see, when you overlay phishing attempts with compromised credentials you typically see corresponding spikes in compromised email accounts. In the graph below the orange line represents the most recent weekly data on number of reported phishing attempts on campus and the blue line represents the number of compromised email accounts from that same week.

In a recent news article, it was shown that a government backed organization was using phishing to compromise credentials and steal research data. It’s not just marketable identities or credit card numbers anymore.

The UW-Madison Office of Cybersecurity contains a Security Education, Training, and Awareness (SETA) group intended to educate and improve institutional user competence about how to avoid falling victim to cybersecurity threats. MacEwan University’s experience with social engineering is not uncommon and poses a serious threat to higher education institutions, just like UW-Madison. Since they house a great deal and wide range of information, they are prime targets for attacks. From social security numbers to research data to financial aid information, we all must do our part in being careful to protect this private information.

So, what is social engineering?

Social engineering is the exploitation of human nature to gain confidential information. Rather than hacking, social engineers pose as reputable people or organizations to utilize our willingness to trust; something technical security controls cannot protect against. Some of the common tactics they use are phishing, vishing, and smishing. Phishing is the use of fraudulent emails and websites to trick people into disclosing private information like usernames, passwords, credit card numbers, or social security numbers. Vishing and smishing are additional forms of social engineering. Vishing uses telephone calls (voice) to impersonate individuals or organizations, while smishing uses fraudulent SMS texts on a mobile phone.

How to spot the phish

One thing you can do to help protect yourself from these attacks is to know the several ways to recognize these phishing attempts. Some warning signs to look for include:

- Unsolicited messages that ask you to update, confirm, or reveal personal identity information

- Urgency in the message (e.g., “Your account has been temporarily disabled. If we don’t receive your account verification within 72 hours, your account will be further locked down.”)

- Unusual “From” or “Reply-To” email addresses

- Links in emails, especially if the URL doesn’t match the name of the institution it allegedly represents

- Websites that don’t have an “s” after “http//,” indicating it is not a secure site

- Messages that contain grammatical and/or spelling errors

- Emails that are not digitally signed

Phishing for a cause

One way that universities are preventing harmful phishing attacks is through internal phishing awareness campaigns. These campaigns are internal tests conducted by the University in a safe environment, or by a third party, that simulates a phishing attack. Although these phishing campaigns might seem like they are trying to trick you, they actually benefit our institutions in a variety of ways. First, they can be a learning experience for students and staff who fall for the simulated attack. Without the risk that real attacks impose, individuals can self-identify if they need further training and should seek out their local campus IT staff. Furthermore, these campaigns help assess risk exposure for the university.

The UW-Madison Office of Cybersecurity has been running internal phishing campaigns for several campus divisions over the past four years. During the first two years (2014-2016) of these campaigns, the average Click-Through Rate (CTR) was around 10%. We have seen a marked decrease in CTR from late 2016-present (around 4% on average). The success of UW-Madison’s phishing awareness program inspired UW System Administration to formalize phishing awareness as part of a recommended security awareness program.

Please note that UW-Madison will never ask you to disclose Personally Identifiable Information (PII), Payment Card Information (PCI), or Protected Health Information (PHI) via email. If you are unsure whether an email or message is valid, do not respond. Contact your local IT representative or report it to the UW-Madison Office of Cybersecurity at abuse@wisc.edu.